WRITTEN BY: R.J. JENKINS

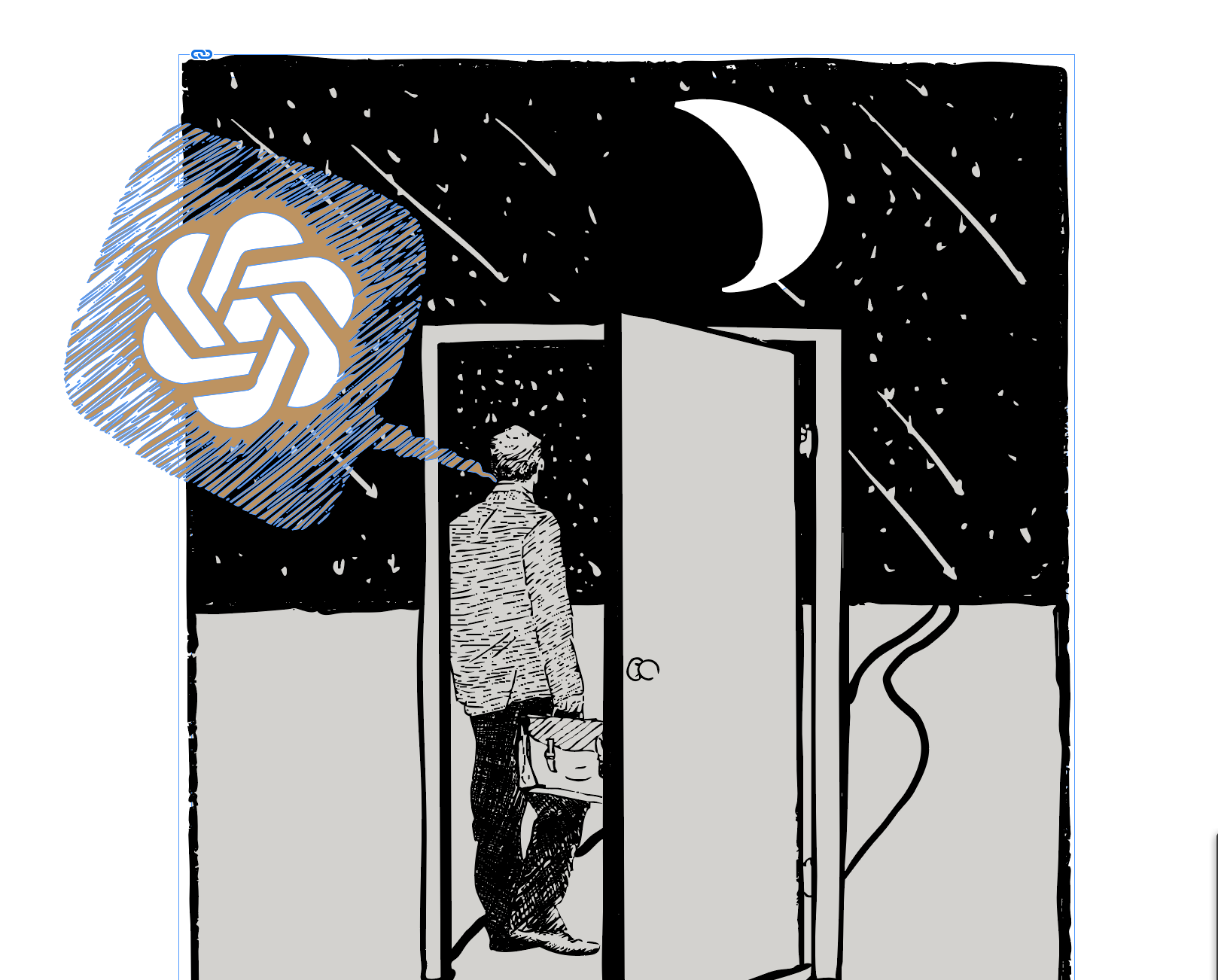

ILLUSTRATION BY: JOSHUA JACOBS

Forgiveness, A Life’s Sentence

…in which a life-long lover of books—and especially, sentences—

responds to ChatGPT’s answers to his questions about books—and especially, sentences

The prompt

This sentence appears in Khaled Hosseini’s novel, The Kite Runner:

“I wondered if that was how forgiveness budded; not with the fanfare of epiphany, but with pain gathering its things, packing up, and slipping away unannounced in the middle of the night.” In 150 words or fewer, tell me why this is such a good sentence.

ChatGPT’s response

This sentence is powerful because it reframes forgiveness in an unexpected, truthful way. Instead of a dramatic moment of revelation, Hosseini describes forgiveness as a quiet, gradual process — pain simply gathering its things and leaving. The metaphor is vivid and human, turning an abstract emotion into something we can picture: pain behaving like a guest who slips away unnoticed. The rhythm of the sentence reinforces this idea, moving from the loud “fanfare of epiphany” to a soft, slow drift, mirroring how healing often unfolds. Emotionally, it resonates because most people don’t experience forgiveness as triumph but as a subtle easing of weight. And thematically, it reflects the central concerns of The Kite Runner: that healing from guilt and trauma rarely arrives with fanfare, but through slow, unglamorous change.

My response to Chat’s response

Another strong response from ChatGPT, especially given the fact that it produced it in approximately 3 seconds. If you’re looking for expeditious excellence — really high quality output produced really quickly — look no further than generative artificial intelligence. “Slow, unglamorous change.” Chef’s kiss.

I will say, however, that this response feels a little more generic and a little safer than some other literary critical responses I’ve seen from Chat. Were I to respond to this same question, I think I would lean further into the allegorization of pain in the sentence. These activities — gathering our things, packing them up, slipping away in the night — are easily imaginable precisely because we’ve all done them. Almost all of us, I’d imagine, can remember a moment in our past when we ourselves have had to do these exact things — perhaps after a relationship-ending conflict, perhaps after a devastating revelation or painful realization, perhaps once we finally learned to love ourselves. By invoking these memories, deeply personal to each of us, the sentence invites us, for a fleeting moment, to be the pain it describes: to imagine it not as an abstract force or emotional sensation, but rather as a figure with which we can empathize. We have all been there, we have all done that, we all know how it feels, and just like that — softly, like a whisper — we are all reading about ourselves.

I would also argue that this sentence highlights something profound about how healing actually works. By depicting pain as an independent character, Hosseini suggests that we cannot command, choreograph, or schedule its departure. We can try to understand it, confront it, outgrow it, or push past it, but pain leaves — if it leaves at all — only when it’s ready, quietly, on its own terms, without necessarily giving us the closure we might want. I think this humbling lack of control is what makes the sentence so resonant and emotionally honest. It forces us to acknowledge that we are at the mercy of our own pain.

R.J. Jenkins’ favorite local charity is the

Marion Literacy Council.

Learn more at marionliteracy.org